Written by Sheena Luke and Silas Rodriguez

Robert Moses, an American public official, was one of the most powerful people in New York during the mid-twentieth century. He is responsible for multiple architectural projects in the city. The legacy his structures left is one that often completely disrupted the surrounding community and people. One of his projects is the Brooklyn-Queen Expressway which was designed to cut a trench between the low-income neighborhood of South Brooklyn. This specific project caused a disconnect in the community and the neighborhood of Williamsburg. The community became territorial as violence and drug use within neighborhoods increased.

To counter the effects of the BQE, community activists and stakeholders created the BQGreen project. The project strives to reconnect the neighborhood of Williamsburg and reverse the pernicious effects that the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway has had on the community. The BQGreen aim is to install four and a half acres of green park space over a segment of the BQE. This approach will not only unite the neighborhood but also address the high asthma rates the expressway has caused. Though the process of achieving this goal will not be easy, the BQGreen team fully pushes to oversee the success of the project.

The biggest question for many with this project is: How could it possibly get done? But before answering this, we have to understand why BQGreen came to be in the first place. To help answer our questions, WHSAD freshman, Sheena Luke, and I spoke with one of the leaders of BQGreen, former deputy borough president of Brooklyn and Williamsburg native, Diana Reyna. In an interview that was as informative as it was uplifting, Ms. Reyna discussed the intricacies of the community’s relationship with politics, and how, by working together, this project is far from a pipe dream. The idea originally was from Diana herself: “When I was a child the question to us was, if you could change one thing about your community, what would it be?” This is something that New York neighborhoods are asked prior to rezoning. Rezoning as defined by Webster, “begins to designate (a zone or zones of a city, town, or borough) for a new purpose or use through a change in the applicable zoning regulations.” Now during the 2005 rezoning of the neighborhood many good things were accomplished, though one thing was left out; that being open space as the rezoners didn’t recognize any community need for it, a mistake that still stings Diana years later. Williamsburg is what Diana referred to as a “tree desert”. Essentially this means that an area doesn’t have enough trees to offset the carbon emissions. Scientists have concluded that carbon emissions are linked to asthma rates in children, and so it’s no surprise that Williamsburg, a community divided by one of the busiest expressways in the city, suffers from high asthma rates in comparison to other parts of New York. Brooklyn is notorious for this as other parts such as downtown Brooklyn have startlingly high asthma rates as well.

Asthma, however, is the tip of the iceberg when it comes to problems caused by air quality. There is quite literally a constant smog over the community, as structures like the BQE and above ground trains are intrusive and release unhealthy emission from both above and below. While there isn’t a proper scientific study on Williamsburg specifically, reason would have one believe that underserved places like areas in Brooklyn that are surrounded by a lot of smog would have higher rates of other diseases and illnesses linked to it, such as cancer, heart disease, or even impaired brain development. So for many behind the project, BQGreen is more than just a park to them.

Though again the biggest question remains: How does BQGreen get off the ground? The short answer from them is community involvement. While that sounds about as cliche as it gets, after speaking with Diana, it is a lot more plausible than one might think. When asked how we get this done she answered, “Taking ownership beyond one person is crucial because it’s a community that will get this done… We have to engage our government.” Unsurprisingly, the reception of BQGreen by the community was less than welcoming. The same questions arose: Is it really plausible for a community that has never gotten the attention of politicians, to now get them to put a park on an expressway? This is where the process starts to get hard. “We rebuilt this community. But we have to strive for more,” said Diana. Something like BQGreen requires a lot of logistics. You need the chance to get the support from the state and the municipality to achieve the working benefits. You’ll need all the proper clearance and funding, and of course, the blueprint which folds neatly into WHSAD students’ specialty of architecture.

She started talking of the power of being civically involved, and while these sort of terms usually get followed by eye rolls, there is legitimacy in the power of communities, as is proven by many of the project’s supporters. Regardless of methodology, there are many ways to be able to impact your environment beyond the conventional methods. As said best by Diana, “Healing comes in all facets.” And some Natives of Williamsburg are starting to push for change.

While Diana is a huge part of this project she isn’t the only person in the community working hard to make this a reality. To highlight a group of individuals, take the El Puente coalition in Williamsburg. El Puente is a non profit art and social justice organization and was founded in 1982. They originally were composed of Latinx youth to combat the growing gang violence in Williamsburg. It was a way for teens to get away from the noise and try and do good in the community. As things got better, they branched out and formed the “Toxic Avengers”, another group meant to fix the situation of environmental damage done to the community by helping educate the youth. And when they focused their attention on asthma rates, it was no coincidence they would be involved in this project. They have tackled numerous issues such as education, providing essentials during Hurricane Maria, raising thousands of dollars for AIDS awareness, healthcare quality and vaccines. The list is endless. The point is El Puente has been a testament to what a small group of people can accomplish, and is exactly what Diana talks about when in regards to community involvement. Groups like this are why optimism is so high for this project. And though many still may have not heard of what some are trying to do with the BQGreen project, the goal is to raise awareness for it to eventually have their voices heard.

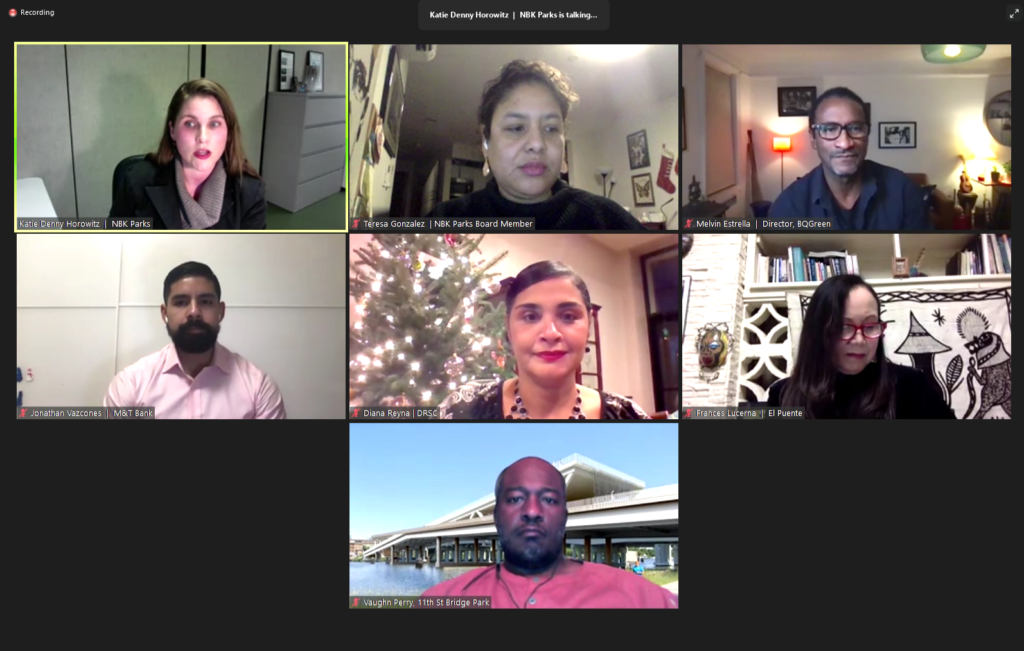

On December 8th, 2020, a panel series was hosted to introduce the BQGreen project. The panelists included; Diana Reyna; Melvin Estrella, Director of the BQGreen film shown below; Teresa Gonzalez, partner at Bolton St. Johns and the cofounder of DalyGonzalez; Jonathan Valzcones, Assistant vice president – Community Reinvestment at MT Bank; Vaughn Perry, equitable Development Manager for 11th street Bridge Park; and Frances Lucerna, President of El Puente. All big players in getting the project off the ground.

Click here to view the BQGreen short film by Melvin Estrella

The Webinar’s purpose was simply to bring further awareness of BQGreen to the community. The entirety of WHSAD was invited to the webinar to learn more about the project and considering WHSAD is in Williamsburg and is centered around architecture, the pairing seems right. Every person there plays an important part in their community. There are more ways to impact the community beyond the conventional methods. Take Johnathan Valzcones for example, who works to secure investments for the community from philanthropists. Or Teresa Gonzalez whose organization, “Daly Gonzalez”, works to provide government, investor and realty support for the community. Slowly but surely the project is garnering the attention of the borough of Brooklyn, and as Diana hopes, to eventually capture the attention of the council board to take the project seriously.

For more information on the BQGreen visit their website: